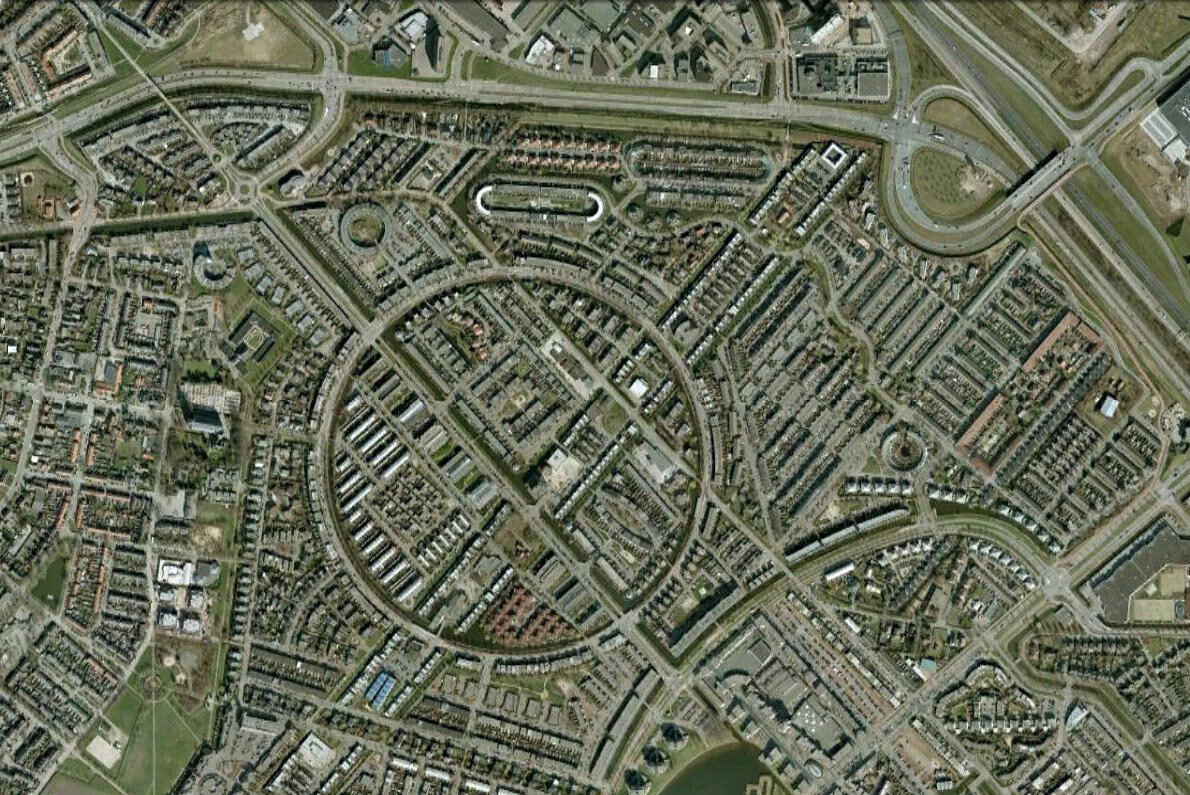

Since 2008, Studio Hartzema has been studying specifically the design of infrastructural networks and the way in which roads influence our perception. It appears to be an unexplored area in the recent Dutch planning tradition. The Randstad in particular seems to be the victim of this. Despite the space and the abundance of greenery, it is experienced as full and chaotic. Baptised Space Making, explorations are carried out and proposals are made.

The roads of the Randstad are fixed and the landscape is far away. There is much, and much of the same and the realization that there is almost no escape from it. But on balance, the Randstad is one of the most sparsely populated metropolises in the world. The feeling of being full and cluttered is apparently a matter of perception. The perception of our living environment is coloured while driving and traveling. As a result, poor infrastructure and poorly functioning connections directly contribute to the experience of lack of space.

Infrastructure and ideology

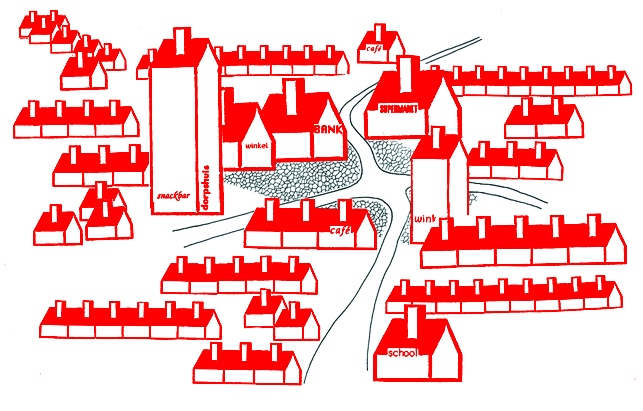

Roads are the long lasting basis of every city. Roads organize our space and describe the relations within the society. In different cultures, the expressiveness of infrastructure has been recognized and consciously used. Thanks to Thomas Jefferson at the end of the 18th century, the United States has a street grid to show that all Americans are basically equal. In France, the infrastructure contributes to Paris’ position as an absolute centrepiece. In Paris itself, the story of the city is told through generous boulevards that put important buildings in place and thus endorse the social hierarchy. In Germany, since the 30s of the last century, all motorways have avoided the cities, so that the suggestion of an endless Arcadia is aroused. The road as a cultural mirror.

The roads of the Randstad show a culture from the bottom up

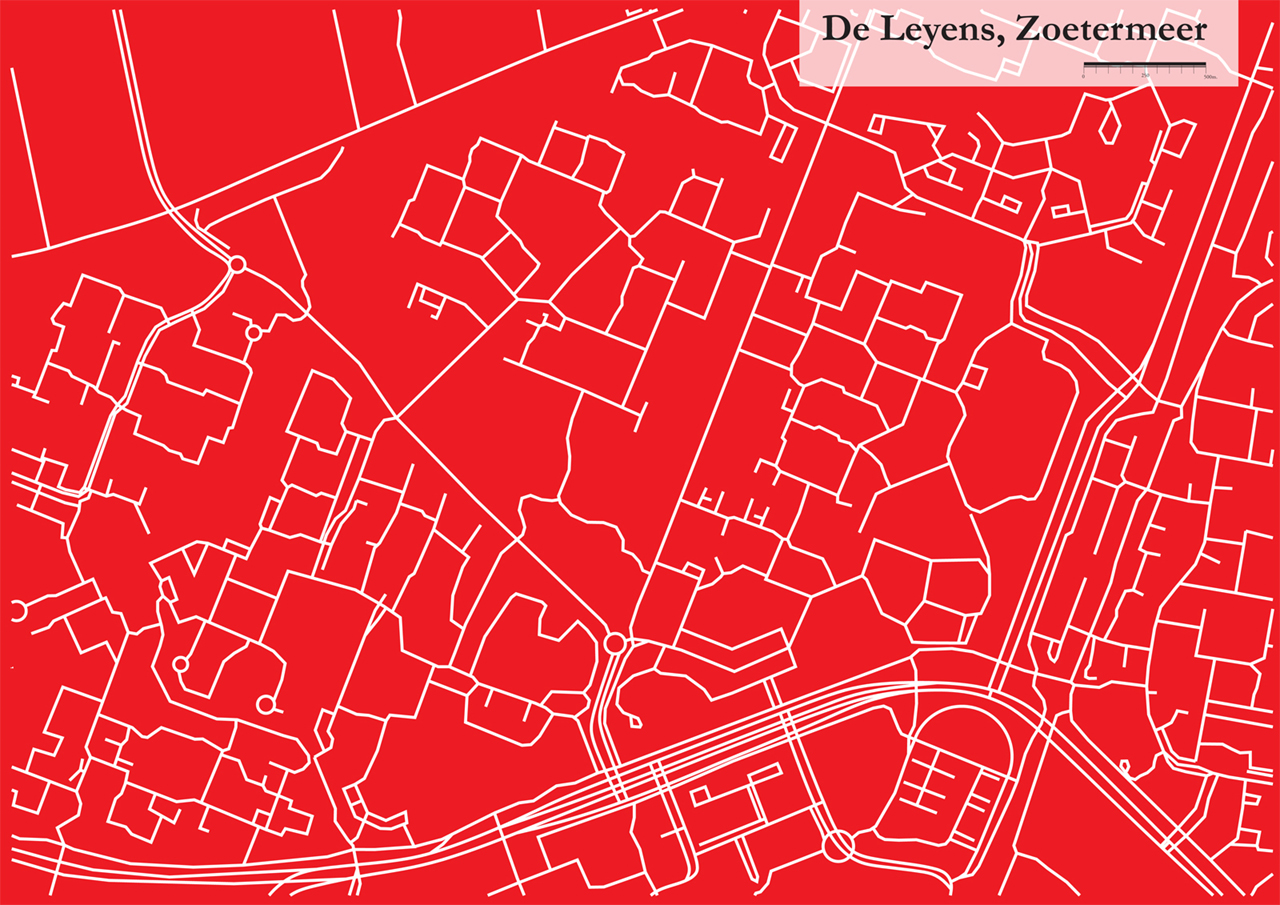

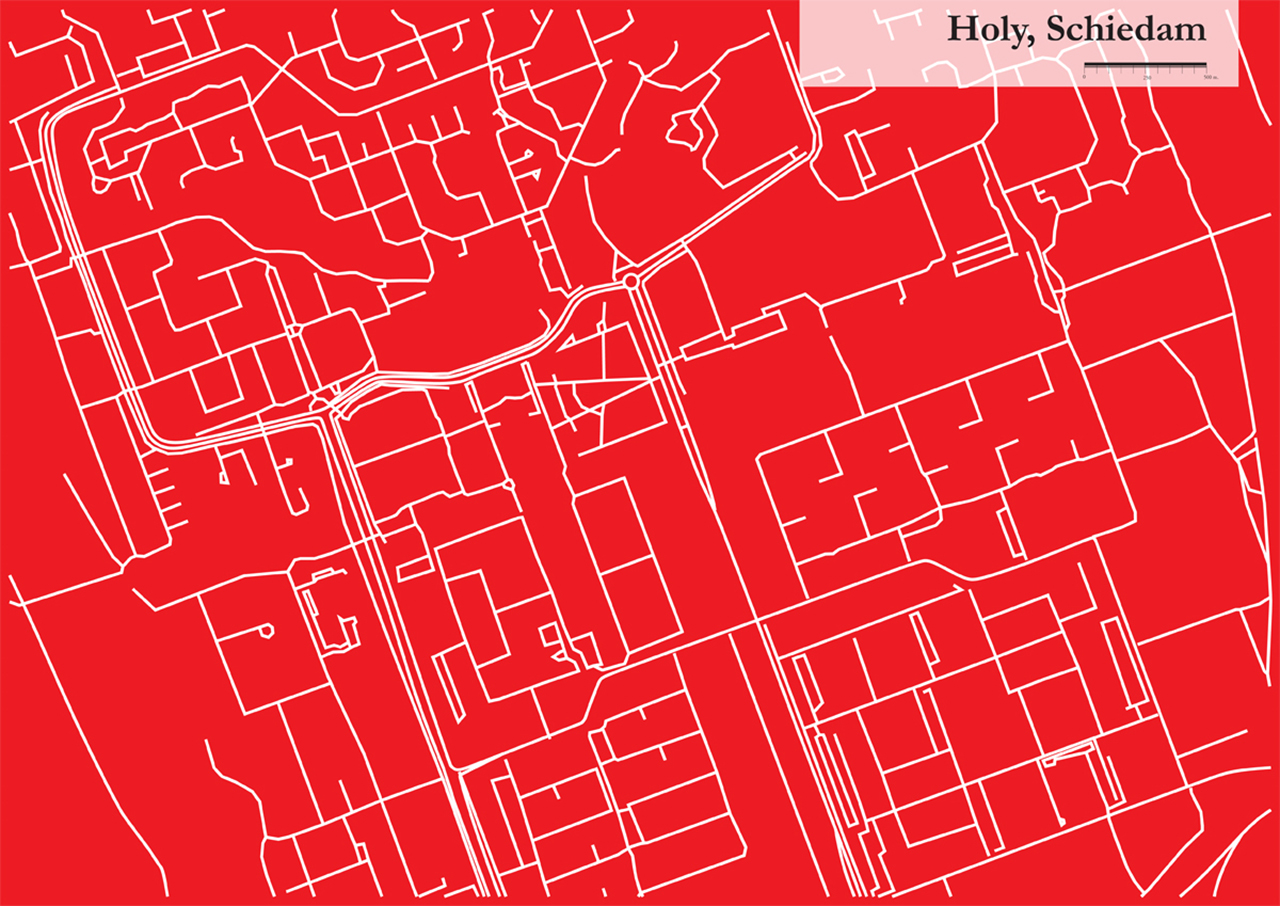

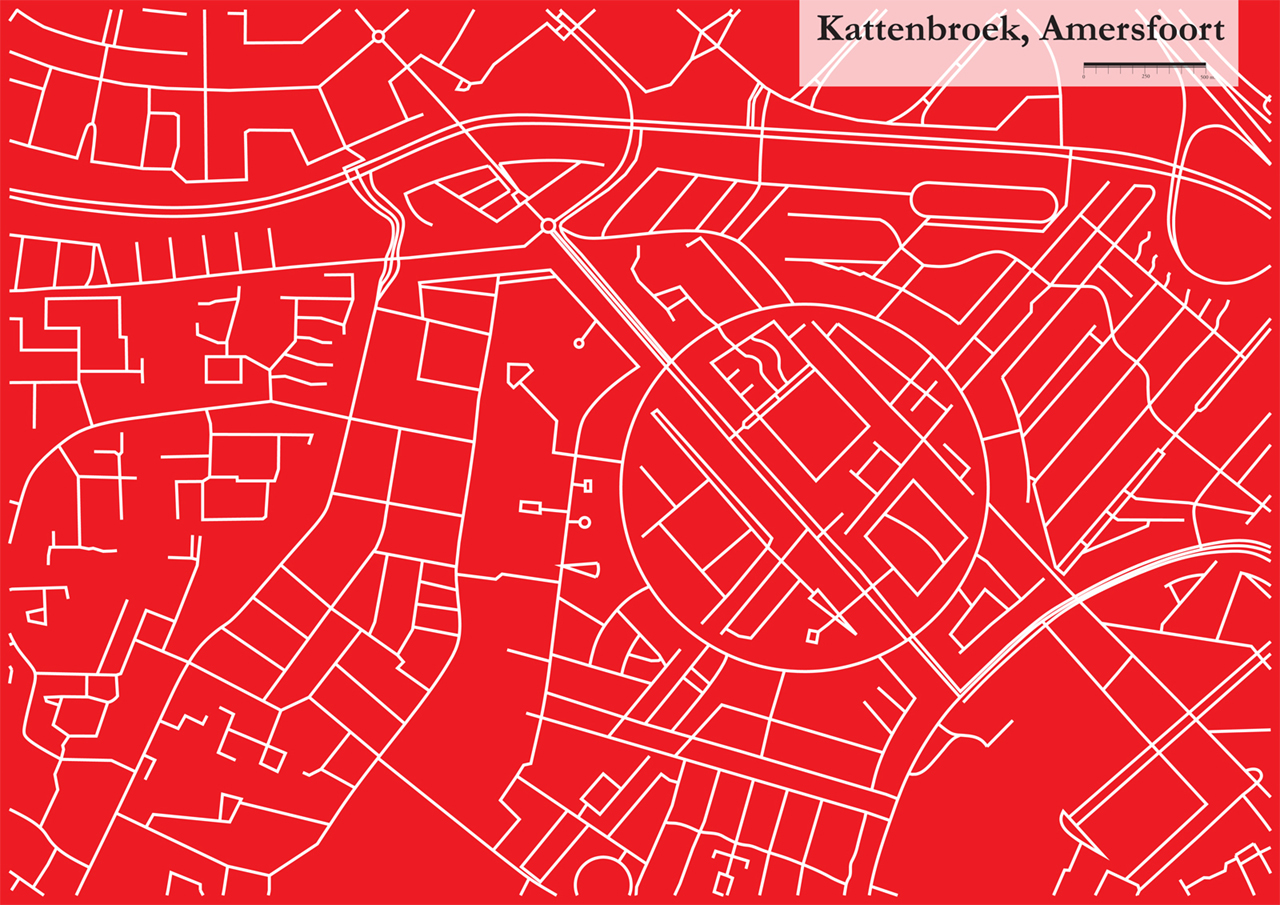

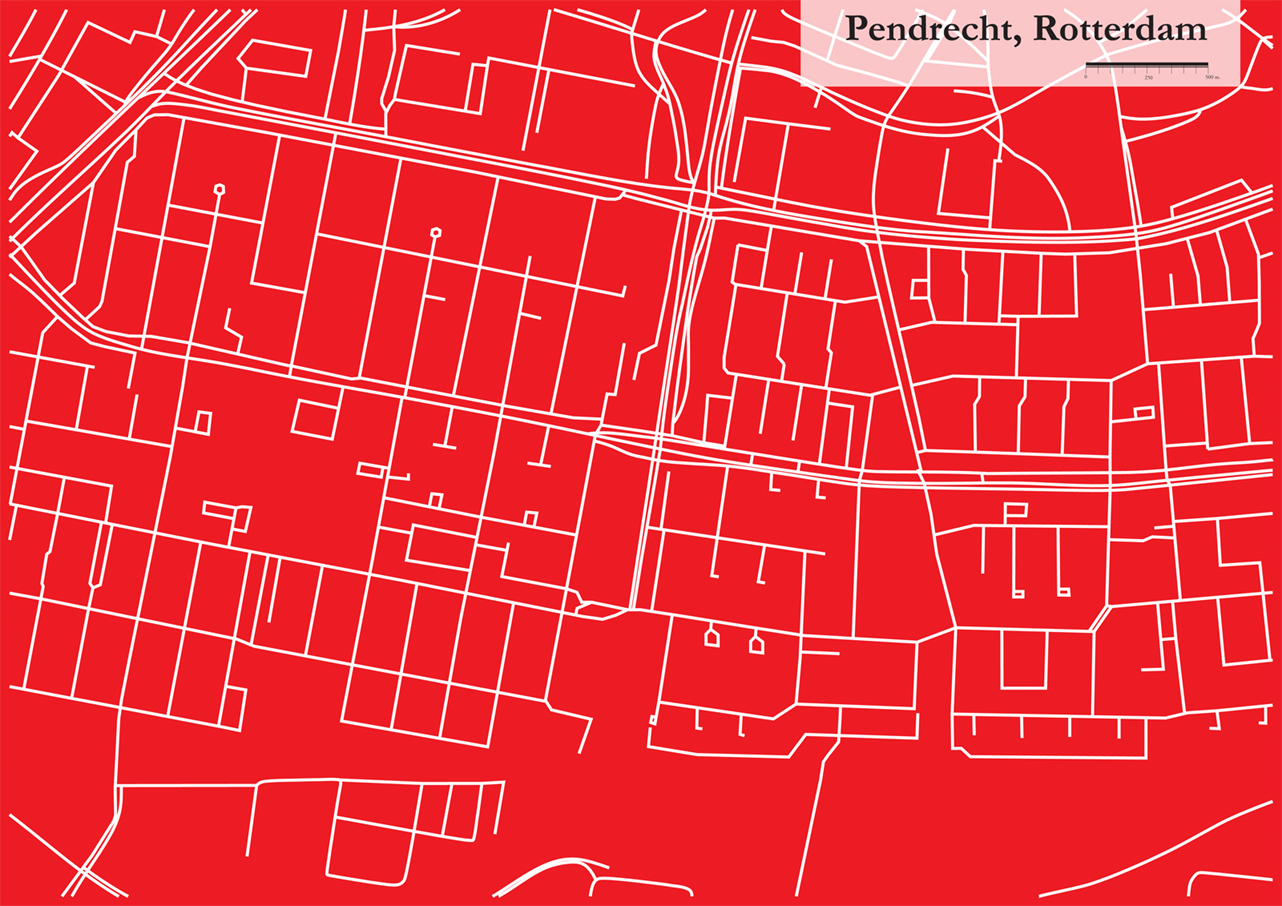

Could it be that, if an ideology can express itself through the pattern of roads, then conversely, it could also be seen from the streets that it lacks a clear vision? After all, there is no part of the Randstad that has not been planned, so time and again it is chosen by designing connections how a specific area should relate to its environment and the bigger picture. Analysis of the road structure should then, as mentioned, betray that our country lacks a clear identity or central control. The road structure of the Randstad could show what generations of car drivers and planners have experienced; the Randstad is not easy to forge into a unity. It turns out that roads, at all scales, contribute to fragmentation of the Randstad and its components rather than to integrality.

This reveals our identity: it is not national, but can only be described on a smaller scale, that of involvement in the collective, the local group. Communities of corresponding interests, precisely named, clearly defined and independent. These ideals can be spatially translated into the sheltered commonality of neighbourhoods, districts and business areas. The Randstad has thus become a kaleidoscopic and peaceful coexistence of 1001 sub-plans without directly identifiable interdependence. There is necessarily physical distance between these areas, and if there is none, it is constructed by a cumbersome road structure. It is exactly what every motorist can retell.

The so-called cluttering is a problem of the lack of structure. Our proverbial powerful planning tradition is particularly evident in the realisation of area developments. On this intermediate scale, construction assignments have been worked on energetically for decades within a precisely defined planning area, with framed responsibilities and a concrete planning horizon. It is striking that the infrastructure is used as a means to make developments possible but at the same time to limit them. Each development is more or less self-contained.

Space for the Randstad

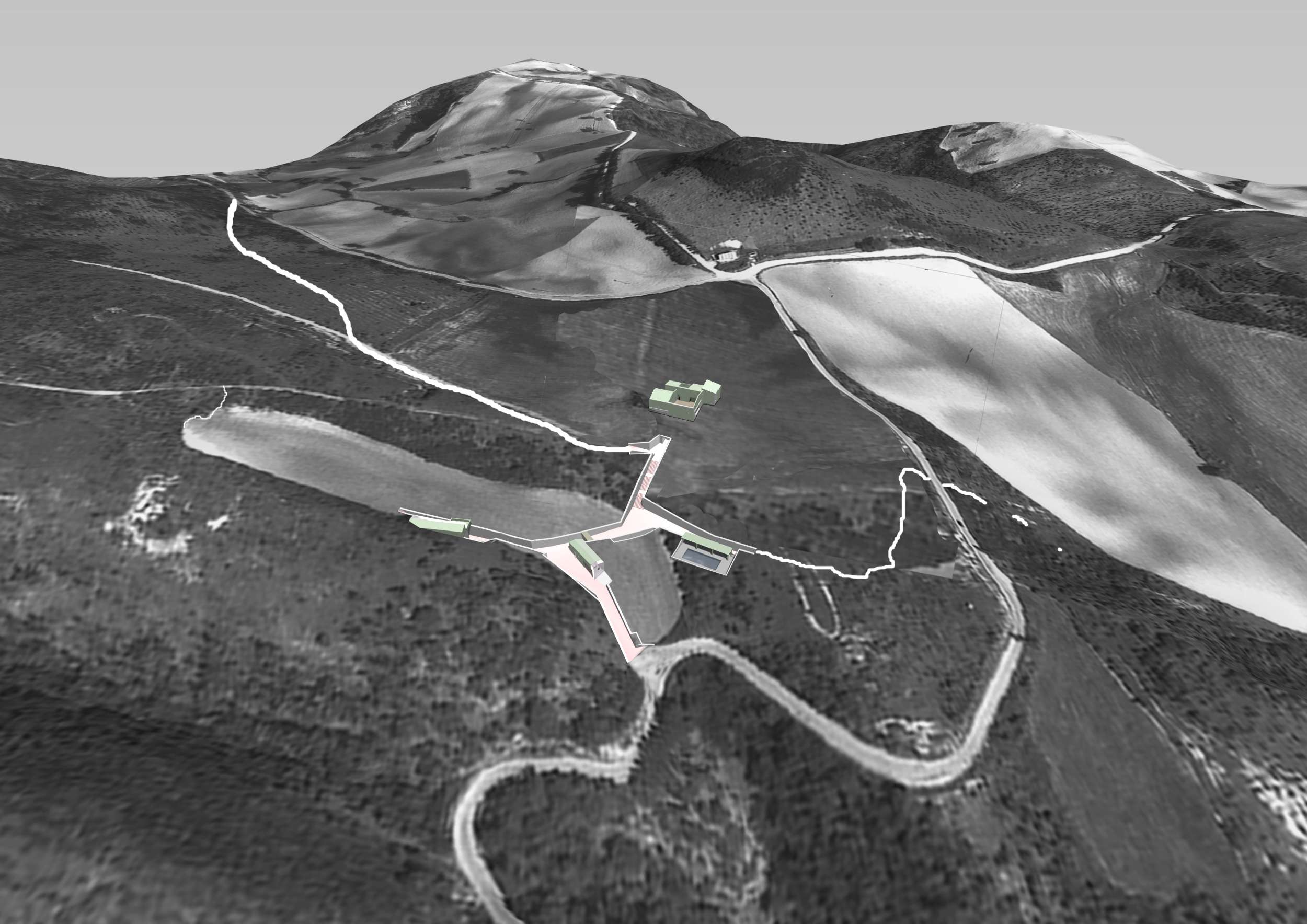

The result is that little by little it is becoming clear that this tradition of optimized sub-plans requires a coherent spatial concept. The amount of sub-plans is starting to grow over our heads. As the Randstad grows, the demand placed on its binding and location-determining capacity is therefore increasing. Especially in the Randstad with its amalgam appearance of coexisting municipalities, there is a growing need for structure and territorial readability.

‘Room for the Randstad’ therefore means thinking in structures. It examines the Randstad and proposes a pragmatic Dutch and at the same time optimistic approach to shaping the long lines and patterns of infrastructure. This vision contributes to controlling the fragmentation of this part of the Netherlands, it makes the Randstad more understandable and gives it air. It makes it possible to come out in unison without neglecting the unique parts.